The Child Murder That Started the Poison Candy Panic

Halloween is an immensely popular holiday in America — some 70% of us celebrate it, spending about $9 billion on candy, costumes, and decorations. The holiday incorporates traditions dating back to the ancient Celts, as well as newer and uniquely American practices.

One of the newest of these American practices, dating back to the 1980s, is the “safe trick-or-treat” or “trunk or treat,” where churches, shopping malls, and other community organizations host Halloween events where kids can come and get their candy in a supposedly safe environment. In addition, many local police departments set up places where trick-or-treat candy can be X-rayed or otherwise inspected.

The assumption behind these events is that trick-or-treat candy from the neighbors might be poisoned, contain illegal drugs, or have razor blades hidden inside. But where did this fear come from? Several places, but one particularly tragic case is what may have started it all.

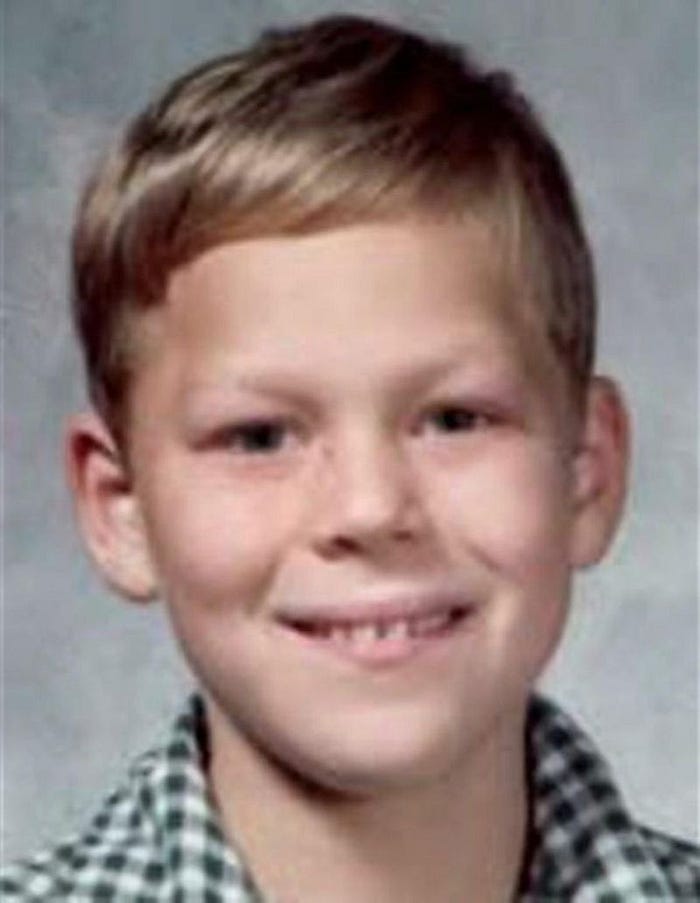

Deer Park, Texas. Oct. 31, 1974: Ronald O’Bryan calls 911 and tells dispatchers that his 8-year-old son, Timothy, has eaten poisoned candy.

Ronald and his neighbor, Jim Bates, had taken their children trick-or-treating earlier that rainy evening. At each house, Jim would wait at the sidewalk while Ronald would walk with the kids up to the front door. Jim remembered that at one house in particular, the lights were off and it seemed like no one was home. The kids were too impatient to wait around, he said, so they ran ahead to the next house.

However, while Jim followed the group of kids, he said Ronald went around the corner of the porch, where it was too dark to see. In a few moments he caught up with them, holding a handful of large Pixy Stix, which he gave to each of the kids. Ronald told Jim that the residents of the darkened house had handed him the candy from the side door after the kids had left.

Once the group returned home, Ronald gave one of the Pixy Stix to a 10-year-old he recognized from his church.

But the only one to eat the Pixy Stix was Timothy. He asked to eat the candy right before bed. He had difficulty opening the package, so his father helped him get it open. Right away, Timothy complained that the candy tasted bitter. So Ronald gave him some Kool-Aid to wash away the taste. Timothy then said that his stomach hurt, and then began vomiting and convulsing.

That’s when his father dialled 911.

Timothy’s autopsy showed he had died from cyanide poisoning; he had enough in his system to kill two adults. It also showed that the cyanide had come from the Pixy Stix.

News that a young boy had died from poisoned candy immediately sent Deer Park’s parents into a panic. Several of them turned their kids’ trick-or-treat candy in to the police, fearing it was also poisoned.

Police moved quickly to find the other Pixy Stix. None of the other kids in their group had eaten theirs, though one boy had tried to — but thankfully, he hadn’t been able to open the package.

Tests showed that the tops of the candies’ packaging had been cut off, cyanide poured inside, then they had been resealed with a staple. Each of the uneaten candies had enough cyanide in them to kill three to four adults.

Such careful work, done on individual candy packaging, wasn’t likely to have been done at the plant or store. The poisoning had to have been done by someone after they had purchased the candy.

Ronald at first said he couldn’t remember where the kids had gotten the Pixy Stix — this despite the fact that the group had only gone trick-or-treating on two streets because of the rain. And none of the residents on those streets had given out Pixy Stix.

On the third trip through the neighborhood, he finally pointed out the house he claimed they had come from. However, the homeowner, an air traffic controller, was quickly ruled out as a suspect, thanks to almost 200 witnesses verifying that he was at work at the time.

Now Ronald O’Bryan was just as quickly becoming the prime suspect. Though he was a deacon and sang in the choir at his church, some digging uncovered that Ronald was in some financial trouble — $100,000 worth of debt, for one. He wasn’t able to hold down a job for more than a few months. His car was about to be repossessed, and his home, foreclosed upon. He was in default on multiple bank loans. And he was on the verge of being fired from his job because he was suspected of theft.

Despite this, his co-workers would later testify that he boasted to them that his finances were about to make a dramatic turnaround.

At the same time, he was becoming very interested in poisons. He asked one of the customers at his job, a chemist, about cyanide — he wanted to know how much would be needed to kill someone and where to buy it. He even tried to buy cyanide at a chemical supply store in Houston, but changed his mind when he learned the smallest amount he could buy was five pounds.

Then, just days after Timothy’s funeral, an insurance agent called the police with some troubling information. In January of that year, Ronald had taken out $10,000 life-insurance policies on both of his children. In September, he had taken out an additional $20,000 on each of them, despite the objections of the agency. Then, just days before Halloween, he took out yet another $20,000 policy on his children. The day after Timothy’s death, Ronald had called the insurance agency asking how he could collect on those policies.

When police searched Ronald O’Bryan’s house, they found his pocket knife with traces of plastic (like that of the Pixy Stix) and cyanide on the blade. He was arrested Nov. 5, 1974, and charged with one count of capital murder and four counts of attempted murder. He pled not guilty.

The case and trial got national attention, and Ronald began to be known as “the candy man.”

On June 3, 1975, the jury only took 46 minutes to convict him on all counts. After an equally short deliberation at his sentencing hearing, he was sentenced to death by lethal injection.

Ronald O’Bryan was executed for the murder of his son March 31, 1984, at the Huntsville Unit in Huntsville, Texas. Hundreds gathered outside the prison, cheering and shouting, “Trick or treat!” Some even threw candy at the anti-death-penalty protesters present.

Ronald’s execution came a full decade after the poisoning, enough time for the story of little Timothy’s death to start moving out of the realm of a tragic family murder and into the realm of urban legend.

But that is not the end of this dark story.

While Ronald O’Bryan was sitting on death row, in September and October of 1982, someone in Chicago began putting cyanide into bottles of Tylenol, killing seven people. No one was ever caught (though New York City resident James William Lewis was considered the prime suspect). This gruesome act inspired hundreds of copycats around the country, resulting in at least three more deaths (Dale Lehman has a great story about this here).

Perhaps conflating all these poisoning cases, the following year Dear Abby, a nationally syndicated advice column read by thousands, published a Halloween-themed column titled “A Night of Treats, not Tricks.” In that column, Abby warned, “[s]omebody’s child will become violently ill or die after eating poisoned candy or an apple containing a razor blade.”

This was also during the height of the Satanic Panic, so Jack Chick wrote one of his (in)famous tracts about Satanists poisoning Halloween candy in order to make sacrifices to Satan.

But the most likely culprit for spreading and legitimizing the poison candy panic were the news media. News stations across the country weren’t about to let a sensationalist trend pass them by; facts be damned, they ran with it. To this day, nearly every Halloween there’s a segment on the local news about the supposed dangers lurking in trick-or-treat candy — though there are never any actual cases or statistics cited.

All that fear-mongering worked: by 1985, a Washington Post poll showed 60 percent of people were afraid their children would be harmed by trick-or-treat candy.

This even though there is literally no evidence that any kid has ever been poisoned or drugged via their Halloween candy by a random stranger. Not once. In every case, either the drugs actually came from someone the child knew or there wasn’t actually any poison. The few cases of sharp objects are nearly always caught before anyone bites into them, and even those are committed by someone who knows the “victim.”

So the rumors persist. Part of the problem is humans’ selective memory: people hear an initial news story about poisoned or drugged Halloween candy and freak out. But they either don’t hear or don’t remember the follow-up. Only the freak-out gets remembered.

Yet newscasters around the country keep repeating it year after year — or, if not repeating it outright, still promoting the “safe trick-or-treat” events, as though there’s no need to explain why regular old trick-or-treating isn’t safe. The urban legend has been repeated so often, it’s just taken as self-evident now.

Many parents, once they learn that this is basically a myth, still choose to avoid real, neighborhood trick-or-treating for events billed as safe alternatives. But are these events really any safer than your own neighborhood? How do you know the guy handing out candy from the back of his van in the church parking lot, or the teen at the mall, is any safer than your neighbor handing out candy from their own front door?

Halloween is a holiday based on fear. Scary stories and urban legends start to become just a little more solid, a little more real, on this night. But we shouldn’t ruin Halloween over fears based on nothing but an urban legend.